The Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755) was an early champion of representative government whose writings influenced the Founding Fathers and the subsequent framing of the U.S. Constitution. Among many of his popular concepts was the “separation of powers.” As Raymond Aron points out, what was just as important was his belief in the balance of powers.

Accountability is an important safeguard of freedom. So is the opportunity for constructive dissent. As Montesquieu writes: “Whenever we shall find everyone at peace, in a State which calls itself a Republic, we can be sure that there is no liberty there…. ” By “peace” he means the unthinking conformity (or leveling uniformity) of tyranny.

It is also interesting that while the French philosopher outlined numerous differences between monarchy and democracy, the most significant distinction for him was between the moderate implementation of these systems and the emergence of despotism. It is the growth of unlimited powers that endangers any polity, including democracy.

Aron explains that “whereas republican equality is an equality of virtue and of universal participation in the sovereign power, despotic equality is an equality of fear, impotence, and nonparticipation in the sovereign power.” In addition, the trend toward despotism occurs when governments “lose respect for order” and “for those intermediary bodies without which social structure collapses and the absolute power… triumphs over all moderation.”

As it turned out in the case of France, the culmination of despotism occurred not under the traditional monarchy of Montesquieu’s era—flawed though it was—but in the Revolution of 1789-1799. It was a radical “democracy” which took a very different ideological tangent than the American experiment.

In conclusion (says Aron) the “spirit of a nation” is related to the general consensus or “sentiment which sustains a political regime.” Such expectations are “closely related to a nation’s way of life as expressed in its institutions.” In other words, underlying cultural assumptions are just as a important to the success of a republic as its political structures.

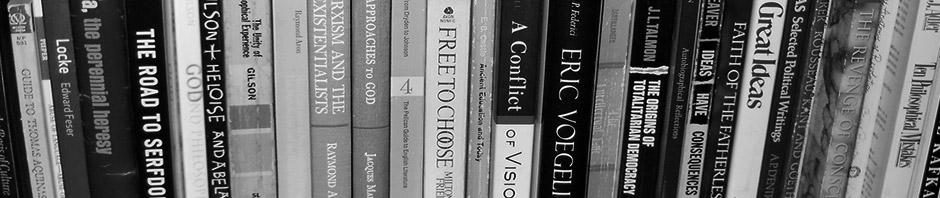

The above comments are based on Aron’s essay on Montesquieu in Main Currents in Sociological Thought, Vol. I (Doubleday Anchor, 1968).